Hopes for treating life-threatening diseases with cells taken from patients' own bodies have suffered a setback after research showed they might trigger severe immune reactions.

The surprise finding will be a hurdle for scientists working on induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, a variety of cell that holds promise for treating conditions as diverse as muscular dystrophy, Parkinson's and heart disease.

Like embryonic stem cells, iPS cells can develop into a range of body tissues, raising the possibility they could be used to grow healthy replacements for organs damaged by accidents or ravaged by disease.

Their creation in 2006 marked a turning point in stem cell research, because iPS cells suffer from none of the ethical issues that plague embryonic stem cells. Instead of being collected from surplus IVF embryos, iPS cells can be made from a patient's own skin cells, by rewinding their biological clocks to a more youthful state using a cocktail of chemicals.

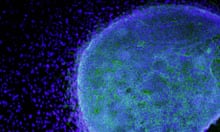

Since iPS cells are genetically identical to their donors' cells, transplants of the cells were not expected to trigger the body's immune defences, but that view is now being questioned.

Writing in the journal Nature, a team led by Yang Xu at the University of California, San Diego, show that iPS cells triggered immune reactions when they were implanted into mice. In some cases, the cells were completely destroyed by the animals' immune systems.

Although the studies were done in rodents, the findings raise doubts over the use of iPS cells in future human therapies. "The assumption that cells derived from iPS cells are totally immune-tolerant has to be reevaluated before considering human trials," Xu said.

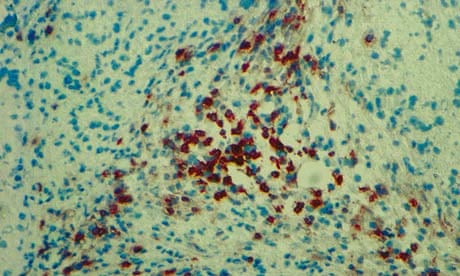

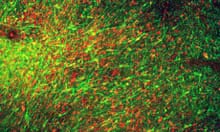

In the study, Xu's team took embryonic stem cells and iPS cells created from mouse tissue using different techniques, and transplanted them into genetically identical mice. The embryonic stem cells did not trigger an immune attack, but the iPS cells did. The most aggressive reactions were against iPS cells created using a virus.

Further tests revealed that the reprogramming process altered the expression of genes in the iPS cells, in some instances triggering the body's immune defences.

In many cases, only some cells appeared to cause an immune reaction, but Dr Xu said it was unclear which cells were the problematic ones. The answer could prove crucial to the future role of iPS cells in medicine.

"If it's only limited to certain cell types, then the others can still be used for cell transplantation without worry of being rejected, but if it's a widespread problem it's another issue. At the moment it is hard to say how big the hurdle is," Xu said.

While it may be possible to screen iPS cells and discard those likely to be rejected by the body, researchers hope to overcome the problem by finding more precise ways to create iPS cells so they hide from the immune system.

Paul Fairchild, director of the Oxford Stem Cell Institute, said nobody would have anticipated the immune rejection problem, but added it was too soon to know the implications for medical therapies based on iPS cells.

"It does beg an important question as to whether the same would happen in humans, but it's premature to suggest it casts a cloud over the whole field. We have no idea if human cells would respond in the same way," he said.

The iPS cells in the latest study might have caused an immune reaction because they were created from embryonic mouse skin cells, which express genes differently to adult skin cells. "If they had started with adult cells they may not have seen an immune response, but we simply don't know," Fairchild added.