The production and the spread of misinformation have become major concerns for scholars, policy makers, and commentators across the world.

Uncertainty and controversy around the COVID–19 pandemic has intensified the debate about misinformation in the last few weeks. “We're not just fighting an epidemic; we're fighting an infodemic”, said WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus. We don’t have new data on how the outbreak is changing news consumption around the world. However, researchers have been investigating how media outlets and technologies shape, mediate, and reflect the global problems of misinformation.

This post provides a short overview of this research with seven highlights that can help us understand how people navigate information (and misinformation) and what role journalism and news can play in a crisis like the current pandemic. It’s important to take into account that the data we are mentioning in this piece precedes the COVID–19 outbreak, and we have previously summarized some of it here.

1. Most people access news through side-doors.

Our research documents the central role that social platforms and search play in the distribution of both information and misinformation online. Despite some variation, this pattern is observed across countries. Side-ways access of news via search engines, social media, or other forms of distributed discovery can obscure the producers of news content and create openings for various purveyors of disinformation. It is critically important that the technology companies that drive so much attention online take steps to reduce the spread of potentially harmful misinformation.

Proportion that say each of these is their main gateway to news

2. News accessed through these side-doors is less trusted than news accessed directly.

While there has been a well-documented decline in trust of news organisations across countries, trust in news accessed via search and social media is notably lower than that approached directly.

Average trust in news overall (42%) across all countries studied in the most recent Digital News Report was higher than reported trust in news from search (33%) and social platforms (23%). Thus, there is plenty of evidence to suggest that people come across both relevant reliable information and various kinds of misinformation while relying on technology companies. However, it is also clear that most people treat much of this information with considerable scepticism, and they are more likely to trust information from news media, especially the news media they routinely use.

Proportion that trust most news from each most of the time

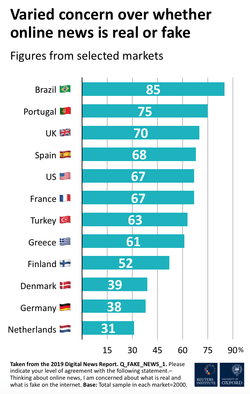

Varied concern over whether online news is real or fake

3. Many people are concerned about their ability to separate what’s real and what’s fake online.

More than half (55%) of the sample across 38 countries in the 2019 Digital News Report reported concern about their ability to separate what is real and fake on the internet. However, that concern varies widely across countries. While 85% of Brazilians say they are worried about online misinformation, that concern is much lower in Germany (38%) and the Netherlands (31%).

There is a real risk that this concern over the authenticity and veracity of information online may be paralyzing as people look for reliable information to inform them about what to do during a crisis like this.

4. People are exposed more to poor journalism than to made-up stories.

Concern vs exposure to several types of misinformation

While audiences express worry over foreign influence operations and fabricated for-profit content, many of the people who have participated in our focus groups in the past have also expressed concern over other types of what they consider to be misinformation, including satire, poor journalism, political propaganda, and some forms of advertising.

Journalists at many news organizations are working really hard to keep people informed, but despite their efforts, much of the public see the line between news and “fake news” as a difference of degree and not a categorical distinction. When asked about their experience with misinformation, audiences we surveyed in 2018 reported greater exposure to what they considered to be examples of political propaganda and poor journalism than to made-up stories, even as they were equally concerned about this type of problem.

While credible information from public authorities and news media will be key to helping people understand and respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, many remain sceptical of politicians and news media for peddling self-interested material that sometimes amounts to outright misinformation.

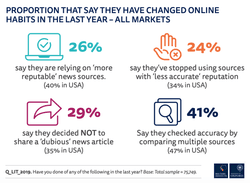

5. Misinformation is encouraging some people to rely on more reputable sources.

There is some indication that persistent concern over misinformation is encouraging a greater awareness of and affinity for trusted news brands. Over a quarter (26%) of global audiences surveyed in early 2019 say they have started relying on what they consider to be ‘more reputable’ sources of news —rising to 36% in Brazil and 40% in the US. A further quarter (24%) said they had stopped using sources with a ‘less accurate reputation,’ with almost a third (29%) deciding not to share a potentially inaccurate news article. This is consistent with reports in recent days from widely trusted news media, such as the BBC, Channel 4, and some newspapers in the UK, who say their audience has increased in recent days.

Proportion that say they have changed online habits in the past year

6. Social media can disseminate misinformation on health issues.

In several European countries, we have found in the past that sites that regularly shared misinformation had far less online traffic than established news outlets. However, in some cases, a small number of these problematic sites —some of which focused on health-related issues— generated a very large number of Facebook interactions, even larger than some of the established news outlets. This demonstrates how social media can be platforms for the wide dissemination of misinformation, even as elected officials, public authorities, and news media are using these platforms to share information about the Coronavirus crisis.

7. The language of risk encourages appropriate action.

Our research on climate change communication has examined the value in news outlets adopting the language of risk rather than the language of uncertainty when reporting on complex topics in science, technology, and health. As our research showed in 2013 (examining coverage of climate change), scientific uncertainty is often misunderstood or misinterpreted as ignorance by both the general public and journalists. Many people fail to recognise the distinction between ‘school science’, which is a source of solid facts and reliable understanding, and ‘research science’ where uncertainty is engrained and is often the impetus for further investigation.

Given the recency of the outbreak, much of the best available science about COVID-19 is uncertain. However, as the language of uncertainty can suggest that action is best delayed until certainty is achieved —which may never happen— public authorities and news media may consider embracing the language of risk and methods like simulation. Adopting the language of risk can encourage consideration of a range of options grounded in an analysis of risks and rewards.

If you want to know more…

This opinion piece reflects the views of the author, and does not necessarily reflect the position of the Oxford Martin School or the University of Oxford. Any errors or omissions are those of the author.