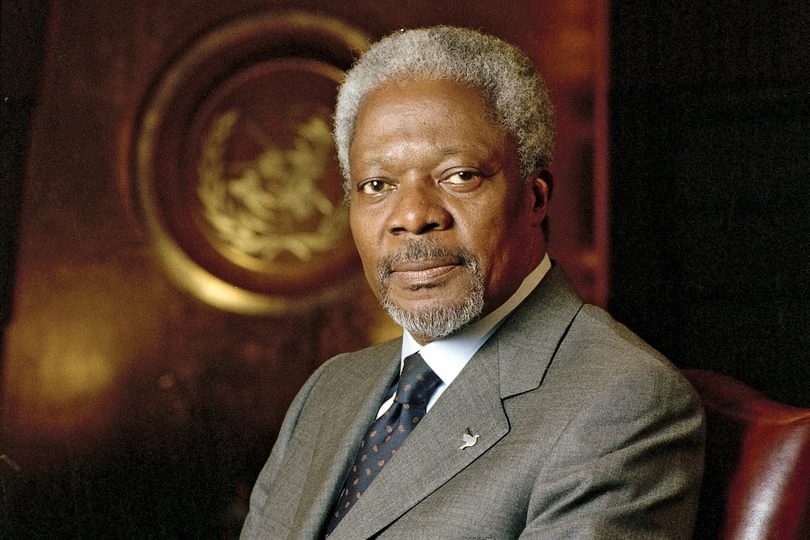

Jennifer Welsh, Director of the Oxford Institute for Ethics, Law and Armed Conflict, comments on the patience and impartiality that makes Kofi Annan a super negotiator

Spare a thought for the tireless Kofi Annan, criss-crossing the globe in search of a negotiated solution to the current crisis in Syria. Since finishing his tenure as secretary general of the United Nations, Annan has been mentioned most often when those exasperated with seemingly intractable situations are in search of a mediator. It’s an interesting sign of the times that there are so few figures seen to possess the qualities of patience and impartiality necessary for mediation.

Annan played a critical role in stemming the violence that erupted after Kenya’s disputed national elections in late 2007 (which led to approximately 1,200 deaths and the displacement of over 600,000 people). As the ethnically motivated attacks threatened to spiral out of control, the African Union sent in a number of potential mediators (including former South African bishop Desmond Tutu, and the former president of Ghana, John Kufuor). But it was only when Annan arrived and the international community focused on a single negotiation process that the talks between the two rival political leaders (President Mwai Kibaki and opposition leader Raila Odinga) finally got underway. After roughly 40 days of hard bargaining – underpinned by threats to impose targeted sanctions and cut off aid – a deal (the National Accord and Reconciliation Act) was reached, which included a power-sharing agreement and the establishment of a justice and reconciliation commission. The key measures that facilitated the accord included sequestering the two sides at a retreat at the Kilaguni Lodge in Kenya’s Tsavo West National Park, Annan’s well-timed interventions with the two principals, and temporarily suspending the talks when negotiations appeared to be deadlocked.

The question capturing minds at present, of course, is whether Annan’s considerable skills and experience (as demonstrated in Kenya) can lead the rival sides in Syria to accept the peace plan – now dubbed the Annan Peace Plan. While plenty of observers, including U.S. Senator John McCain, want more forceful measures to kick into action, others would still like to give diplomacy a chance.

In analyzing why negotiations succeeded in Kenya, the Centre for International Conflict Resolution at Columbia University identified a number of more general factors (beyond Annan’s personal qualities) that were crucial to bringing about a peaceful resolution of the dispute: a single mediation process fully supported by the international community; strong engagement by civil society (whose various members came together under an umbrella movement called Kenyans for Peace with Truth and Justice); the division of issues into short-term and long-term categories; a well-planned media strategy; and an understanding of peace as a process rather than an event, among other things.

It’s not hard to see that few (if any) of these conditions are present in Syria. For example, while the international community is less divided than it was two months ago, it is still sending mixed signals to Syrian officials about whether/how the opposition groups in the country are being supported by the outside world. At a more fundamental level, however, the environment for negotiation is less hospitable in this crisis, making it harder to get people to sit around the proverbial “table.” As former British foreign office minister Lord Malloch Brown recently argued on the BBC, the international community is hamstrung by two trends that it has itself fuelled since the beginning of the 21st century. On the one hand, various western interventions have frequently tipped the balance in favour of opposition groups, leading them to think that as long as they have “right” on their side, the outside world will give them unqualified support. On the other hand, after 9/11, western governments encouraged the view that all opposition rebels were “terrorists” who had to be fought to the bitter end, since they could not be negotiated with. The latter narrative is precisely the one being propagated by the Syrian government. Added to these trends is the growing commitment to accountability for the commission of crimes, which makes it more challenging to create a negotiating strategy that disaggregates issues into “short” and “long” term.

Has the international community forgotten how negotiation works? At present, it seems to think that only one man can make it happen. But the problem in Syria may be too intractable – even for the world’s negotiator.

- Find out more about Jennifer Welsh and her research at the Oxford Institute for Ethics Law and Armed Conflict

This blog first appeared on the Canadian International Council website on April 11.

Image credit UN Photo/John Isaac

This opinion piece reflects the views of the author, and does not necessarily reflect the position of the Oxford Martin School or the University of Oxford. Any errors or omissions are those of the author.