The rapid evolution of HIV, which has allowed the virus to develop resistance to patients' natural immunity, is at the same time slowing the virus's ability to cause AIDS.

The study, which included researchers from the Oxford Martin School's Institute for Emerging Infections, also indicates that people infected by HIV are likely to progress to AIDS more slowly – in other words the virus becomes less 'virulent' – because of widespread access to antiretroviral therapy (ART).

Both processes could make an important contribution to the overall goal of the control and eradication of the HIV epidemic. In 2013, there were a total of 35 million people living with HIV worldwide, according to the World Health Organisation.

The study, funded by the Wellcome Trust and published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Science (PNAS), was led by researchers at Oxford, along with scientists from South Africa, Canada, Tokyo, Harvard University and Microsoft Research.

The research was carried out in Botswana and South Africa, two of the countries that have been worst affected by the HIV epidemic. Researchers enrolled over 2000 women with chronic HIV infection to take part in the study.

The first part of the study looked at whether the interaction between the body's natural immune response and HIV leads to the virus becoming less virulent.

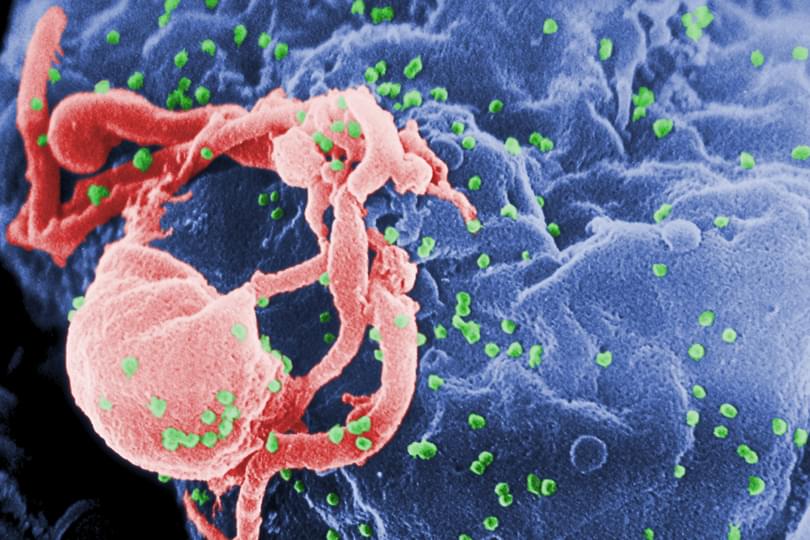

Central to this investigation are proteins in our blood called the human leukocyte antigens (HLA), which enable the immune system to differentiate between the human body's proteins and the proteins of pathogens. People with a gene for a particular HLA protein called HLA-B*57, are known to benefit from a 'protective effect' to HIV. That is, infected patients with the HLA-B*57 gene tend to progress more slowly than usual to AIDS.

This study showed that in Botswana, where HIV has evolved to adapt to HLA-B*57 more than in South Africa, patients no longer benefit from this gene's protective effect. However, the team's data show that the cost of this adaptation to HIV is that the virus' ability to replicate is significantly reduced – making the virus less virulent.

The researchers show that viral adaptation to protective gene variants, such as HLA-B*57, is driving down the virulence of transmitted HIV and is thereby contributing to HIV elimination.

In the second part of the study, the team examined the impact of ART on HIV virulence. They developed a mathematical model which suggested that the way treatment is provided to those with more virulent HIV is accelerating the evolution of HIV viruses with a weaker ability to replicate.

'This research highlights the fact that HIV adaptation to the most effective immune responses we can make against it comes at a significant cost to its ability to replicate,' said lead scientist Professor Phillip Goulder from the University of Oxford. 'Anything we can do to increase the pressure on HIV in this way may allow scientists to reduce the destructive power of HIV over time.'

Mike Turner, Head of Infection and Immunobiology at the Wellcome Trust, which funded the work, said: 'The widespread use of ART is an important step towards the control of HIV. This research is a good example of how further research into HIV and drug resistance can help scientists to eliminate HIV.'