Despite the way that mobile technologies and social networking sites have made it easier to stay in touch with large numbers of acquaintances, a new study has shown that people still put most of their efforts into communicating with small numbers of close friends or relatives, often operating unconscious one-in, one-out policies so that communication patterns remain the same even when friendships change.

“Although social communication is now easier than ever, it seems that our capacity for maintaining emotionally close relationships is finite,” said Felix Reed-Tsochas, Director of the Oxford Martin Programme on Complexity and James Martin Lecturer in Complex Systems at Saïd Business School, University of Oxford.

“While this number varies from person to person, what holds true in all cases is that at any point individuals are able to keep up close relationships with only a small number of people, so that new friendships come at the expense of ‘relegating’ existing friends.”

The research, ‘The persistence of social signatures in human communication’, was conducted by an international team that included Felix Reed-Tsochas and Robin Dunbar from the University of Oxford, Dr Sam Roberts from the University of Chester, and Dr Jari Saramäki from Aalto University, Finland and is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS) today. It combined survey data and detailed data from mobile phone call records that were used to track changes in the communication networks of 24 students in the UK over 18 months as they made the transition from school to university or work.

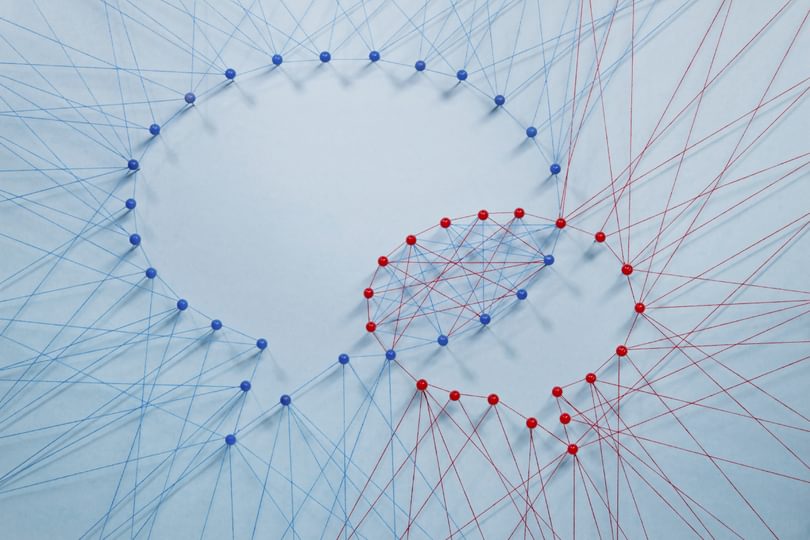

At the beginning of the study, researchers “ranked” members of each participant’s social network (friends and family) according to emotional closeness. They discovered that, in all cases, a small number of top-ranked, emotionally close people received a disproportionately large fraction of calls.

Within this general pattern, however, there was clear individual-level variation. Each participant had a characteristic “social signature” that depicted their particular way of allocating communication across the members of their social network.

The researchers discovered that, even though participants’ relationships changed and they made new friends during the intense transition period between school and university or work, individual social signatures remained stable. Participants continued to make the same number of calls to people according to how they ranked for emotional closeness, although the actual people in their social networks and/or their rankings changed over time.

“As new network members are added, some old network members are either replaced or receive fewer calls,” confirmed Robin Dunbar, Professor of Evolutionary Psychology at the University of Oxford. “This is probably due to a combination of limited time available for communication and the great cognitive and emotional effort required to sustain close relationships. It seems that individuals’ patterns of communication are so prescribed that even the efficiencies provided by some forms of digital communication (in this case, mobile phones) are insufficient to alter them.”

Dr Roberts, from the University of Chester’s Psychology Department explained: “This study used a novel combination of questionnaires and mobile phone data to show that people have a distinctive pattern of communicating with their family and friends, and that this pattern persists even people make new friends as they go to university or work. Our results are likely to reflect limitations in the ability of humans to maintain many emotionally close relationships, both because of limited time and because the emotional capital that individuals can allocate between family members and friends is finite.”