HIV researchers say new analysis of patient data could help to shed light on the phenomenon known as ‘post-treatment control’, where the virus remains undetectable in some patients even after treatment is stopped.

Led by Dr John Frater, Co-Director of the Oxford Martin Institute for Emerging Infections, researchers at Oxford and the University of New South Wales, in collaboration with partner institutions in the UK, Brazil and Italy, analysed data from a patient trial where anti-retroviral therapy was interrupted at 48 weeks.

They found that the way patients’ immune systems initially responded to HIV infection could provide an indication of whether they might go on to achieve an extended period of remission following anti-retroviral therapy (ART). The findings are published today in Nature Communications.

Dr Frater said the analysis could open new avenues for understanding post-treatment control, and eventually HIV-1 eradication.

He said: “Normally, if someone is being treated for HIV infection and they stop their medication, the virus can be detected back in the blood stream within days.

“We have been trying to find out why this is not true all in patients, but that in some people the virus remains undetectable for months, and even years after stopping treatment. Understanding this might help us develop new treatments, and ultimately a cure for HIV infection.

“Our work has identified that there are certain markers on the immune cells of patients which seem to help predict who can stop therapy and stay well. Interestingly, some of these markers have also been shown to be good targets for therapy in some cancers.

“We hope now to find out more about these markers – and others – to discover if new strategies for treating or even curing HIV might be possible.”

ART has dramatically improved life expectancy for people with HIV, but is not a cure, as the infection persists in a latent state in cells. In some cases, however, patients whose ART was commenced at an early stage of infection have gone on to experience ‘remission’ periods of 10 years or more when their treatment is stopped.

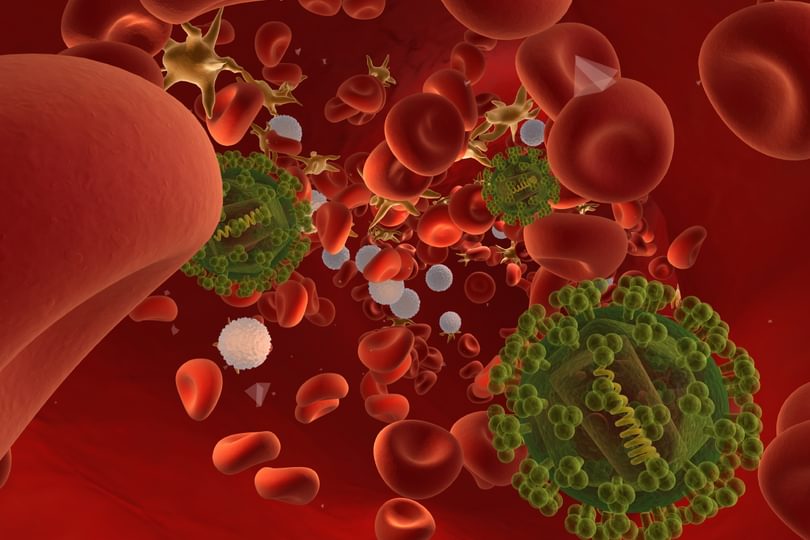

The researchers analysed data from the SPARTAC trial, which began in 2003, and uncovered an association between measurements from T-cells (a type of white blood cell that forms part of the body’s immune system) and how long it took for the virus to return.

Measured at the start of ART, three ‘biomarkers’ were particularly significant in predicting the length of time it would take for the virus to ‘rebound’ after treatment was stopped. Researchers hope the findings will lead to a greater understanding of the mechanisms underlying the post-treatment control state, and potentially to the identification of patients most likely to achieve it.