To bridge growing regional divides, policymakers must foster skills relevant to the hi-tech jobs of the 21st century, argues Oxford Martin Associate Fellow Thor Berger.

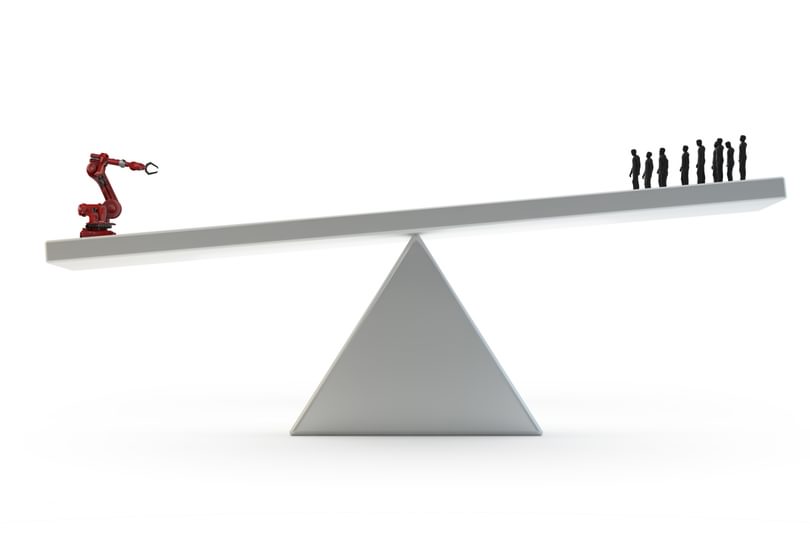

European labour markets have been fundamentally transformed as digital technology has destroyed a wide range of routine jobs, while creating new employment opportunities for highly skilled workers. Recent technological breakthroughs may further exacerbate already rising regional inequalities, with some places pulling ahead and others left behind. A key challenge for policymakers is to devise policies that address the problems of regions that are struggling to adapt to the digital revolution. Policies should focus on improving digital literacy, while also fostering creative and high-level technical skills, enabling lagging areas to transform new technologies into new jobs, which would boost regional competitiveness in the digital age.

Growing digital divides?

Major technological revolutions have always been associated with some places pulling ahead while others are left behind. Over past decades, metropolitan regions such as Berlin, London, and Stockholm have surged ahead by transforming the technologies of the digital revolution into new industries and jobs. At the same time, former manufacturing cities – once the prospering places of the industrial age – have struggled to reinvent themselves as a wide range of routine work has become automated.

Urban areas – with their dense economic activity – are becoming hubs of development because they connect the entrepreneurs, innovators and investors that are required to create jobs in the 21st century. Against the backdrop of increased communication and transportation affordability, the continued importance of physical proximity offered in these cities may seem counterintuitive. However, although mobile devices, social networks, and high-speed wireless broadband makes communication over vast distances possible at nearly zero cost, face-to-face interactions are still the key engine of innovation and growth.

In the long run, regions grow by creating entirely new types of jobs and industries. Whether it is the shift from agricultural work to the assembly line, or the more recent transition from manufacturing towards knowledge-intensive services, the creation of new work has been central to maintain growth. Indeed, the digital revolution has given birth to a wide range of new jobs for app developers, software designers, and search engine optimisers. Places that have managed to create these kinds of jobs have been growing faster as a result. New hi-tech industries, however, tend to be highly concentrated. In the UK, for example, new types of work are typically created in London and spread only slowly to less tech avant-garde places. An important challenge for policymakers is therefore to stimulate the creation of new jobs in areas that have seen the slowest change.

To transition into the jobs of the 21st century, workers need to acquire skills that justify their employment in the digital age. According to estimates from the European commission, there may be as many as 1m vacancies in IT jobs already next year, reflecting a shortfall of workers with high-level technical skills. Regions that manage to either attract workers with such skillsets or provide opportunities for their inhabitants to acquire them are well positioned to see acceleration in growth. Stimulating hi-tech employment growth is important because it constitutes the most dynamic part of the European economy, but also because each additional job in the hi-tech sector creates as many as four additional jobs in the local economy.

Regional policy: people or places?

Policymakers have two options to address regional disparities: invest in people or places. Above all, policies should focus on upgrading the skills of people in disadvantaged areas to raise their productivity. Indeed, a key factor in understanding why some parts of Europe have successfully adapted to the digital revolution is their concentration of skilled workers that implement and invent new technologies that create entirely new types of products, services, or processes – in turn providing meaningful employment opportunities to millions of workers. Vast differences in skills exist within Europe, however, suggesting a potentially large scope for policy action. In particular, fostering skills that have become relatively more valuable over past decades – such as abstract reasoning, creativity, and complex problem-solving – should be a key priority for educational institutions and training providers.

To reduce the hardships and lack of opportunity facing individuals living in stagnating areas, easing intra-European migration and reducing barriers to housing construction in expanding regions are complementary policy levers. Higher mobility may serve to reduce regional differences in unemployment, by increasing the labour supply in areas with low unemployment and reducing it in areas with pervasive joblessness. Moreover, policymakers should ensure that the growth potential of already expanding city regions is not constrained by the supply of housing, which could serve as a drag on national growth.

Alternatively, governments may invest in stagnating places, trying to turn around and revive old manufacturing hubs in decline. However, evidence on the effectiveness of such policy interventions that often entail tax relief or employment subsidies is mixed at best. Rather than creating new jobs, place-based initiatives may instead shift economic activity from elsewhere; although some regions may benefit in relative terms, for the national economy it may be a zero-sum game. Against this background, such policies are unlikely to provide truly transformative change in regions in decline, since they fail to address the fact that a region’s growth potential in the end reflects little more than the creativity and ingenuity of the people that live there.

Decentralisation in the digital age

Digital technology provides unprecedented opportunities to decentralise decision-making processes to regional or metropolitan authorities, providing ways to engage citizens locally while also placing political power closer to the voter. Policymakers should work actively to exploit the open and decentralised nature of digital technology, which could be used to provide more efficient governance and service delivery. In 2014, nearly half of the population in the EU-28 interacted with public authorities via the internet, according to Eurostat. Yet, there is a scope for increased online interaction: in countries such as Italy and Poland, the share is a meager 23 per cent and 27 per cent respectively. An increased use of digital technology to tailor government services to different regional needs is one way to strike a balance between the efficiency gains from a centralised political system and the flexibility of decentralisation.

Regional or local authorities may also more effectively identify and engage with local stakeholders to provide solutions to unique regional challenges. A particularly appealing initiative, supported by the European commission, is the creation and support of digital competence centres that provide the local economy with expertise on digital technology, such as the Fraunhofer Institute in Germany and the Catapult centres in the UK. Facilitating access to new digital technologies, world-class digital experts and support to build bridges between local innovators, firms and customers throughout Europe could serve to substantially raise regional competitiveness. Local policymakers are further particularly well suited to identify the competitive advantages of a region, tailoring the services provided by such competence centres to match the specific requirements of the regional economy.

Yet, steps towards a more decentralised system may exacerbate regional inequalities as recent technological advances are projected to lead to the displacement of workers in a wider range of jobs. Recent estimates by Bruegel, a Belgian thinktank, suggest that nearly half of all European jobs could be automated in the next two decades. In particular, such disruption is likely to disproportionately affect regions that specialise in low-skill work that is becoming susceptible to automation. Against this background, a federal devolution may put increasing fiscal pressure on local governments to deal with costly retraining of displaced workers and rising unemployment. Striking a balance between decentralised decision-making that allows regions to adapt policies to local circumstances and strong central government support for disadvantaged regions should be at the centre of a progressive regional policy agenda.

Outlook

Europe is currently undergoing a phase of rapid technological advancement as digital technologies increasingly permeate the workplace. Although technological advances have displaced workers in a wide range of routine work, digital technology remains a key source of job creation in Europe, with some 100,000 jobs created every year according to the European commission. Metropolitan regions that have been successful in transforming new technologies into new jobs are pulling ahead while others have seen jobs disappear, leading to regional decline. To bridge the growing regional divides, policies should be enacted that allow workers in struggling regions to develop the skills that are needed to transition into the jobs of the 21st century. In addition, regional authorities have an important role to play, in fostering multi-stakeholder partnerships that identify ways to promote skill development and job creation, to deliver growth in the digital age.

- This article was originally published by Policy Network

This opinion piece reflects the views of the author, and does not necessarily reflect the position of the Oxford Martin School or the University of Oxford. Any errors or omissions are those of the author.