In this blog, researchers from the Oxford Martin Systemic Resilience Initiative explore why the UK must reimagine resilience through a systemic lens - recognising the transnational nature of climate shocks and their cascading impacts. Drawing on new evidence and high-level policy roundtables, they argue for a strategic shift: from siloed domestic adaptation to globally integrated, forward-looking resilience planning.

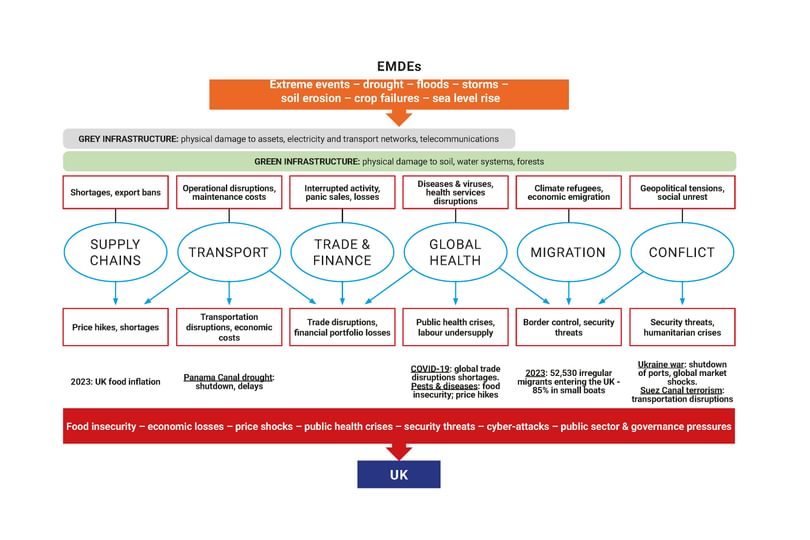

The UK’s security and prosperity are deeply entwined with a complex web of global supply chains – for food, energy, critical minerals, and manufactured goods – which are hugely dependent on transport and other key infrastructure networks globally. Transnational climate risks that affect both grey and green infrastructure in emerging and developing economies (EMDEs) are now cascading across sectors and borders, threatening the key supply chains and macroeconomic stability both in the UK and internationally.

The challenges of transnational climate risks to UK are widely discussed in our recent report, Towards UK Systemic Resilience to International Cascading Climate Risks: The Role of Infrastructure and Supply Chains, which presents new research on the relative influences of different systemic shocks on UK trade and supply chains, with novel methods including the use of high frequency trade data. The findings of this report were discussed, together with key policy solutions, at two high level roundtables with government policymakers, academia and the finance sector at the Chatham House in April 2024 and the Oxford Martin School in May 2025. In this blog post, we outline key messages from the report and the roundtable discussions.

Our recent study highlights important risks to UK resilience

While climate resilience is often discussed in domestic terms (e.g. coastal flooding, infrastructure stress, or energy security), the threats to UK resilience come from abroad receive much less attention. As a nation deeply embedded in global trade, finance, and food systems, the UK is acutely vulnerable to transnational climate risks (TCRs) – multifaceted and cross-border consequences of climate change that extend beyond the territorial boundaries of any one nation.

- Around 95% of UK trade (by volume) is carried at sea, with important dependencies on global maritime chokepoints (narrow, strategic passages with high volumes of maritime traffic) that are prone to different types of risks, such as climate-related extremes, conflict, terrorist attacks, piracy, or blockages. Our report highlights that port disruptions alone could cost the UK $2.5 billion each year, affecting everything from food imports to manufacturing supply chains.

- The UK imports around 42% of the total food consumed, including from water scarce and climate vulnerable countries. Disruptions in global food supply chains can lead to price spikes that affect the most vulnerable populations both in the UK and globally. Our report shows that UK cereal prices are influenced by shocks abroad, estimating that with a consumer price fluctuation of 50-60% above the baseline level can happen following the Ukraine war, an energy shock, trade restrictions and a poor yield year. An energy shock constitutes the dominant driver (on top of a weather shock), which can increase the consumer price index by around 15–20 percent in the median year.

- Natural capital degradation - such as soil erosion and water scarcity - could slash UK GDP by 6% within a decade, acting as a multiplier on other climate risks.

Where the UK Government fails in addressing UK systemic resilience?

The UK’s 2022 Climate Change Risk Assessment (CCRA3) flagged international supply chain risks as a high concern, but the policy response has been slow and incoherent. A 2024 evaluation by the Climate Change Committee found that only a quarter of recommended actions related to international risks had been significantly addressed.

Reflecting these conclusions, discussions with policy and industry experts across sectors highlight that the UK is facing acute governance gaps that undermine resilience. The current resilience governance requires strategic coordination, a shared framework, and a clear institutional home (e.g. the Cabinet Office) with sufficient political weight to coordinate cross-sectoral strategy and engage multiple stakeholders.

Roundtable conversations also highlight the importance of unified narrative to build public and political momentum. Government conversations around resilience often collapse into fiscal debates. Yet, the CCRA3 estimates that if the international climate risks to the UK are not acted upon, this could cost the country over £1 billion annually from 2050 onwards. In the absence of a compelling public narrative, and the UK's withdrawal of overseas development assistance to 0.3% of GNI by 2027, these trade-offs remain politically sensitive. There is thus a pressing need to shift the narrative around resilience – from a one of fear and fiscal challenge to one of opportunity. Investments in resilient infrastructure, smarter supply chains, and climate-compatible development deliver both economic and social returns.

However, new tools and new incentives are needed to unlock this opportunity. For instance, government spending reviews are not currently accounting for cross-border exposure, while the overall ecosystem requires regulatory reform led by a strong government vision, which will create the necessary market shifts for scaling investment in UK and international resilience against TRCs.

Strategic Interventions for Systemic Resilience

Drawing on our report and the expert insights shared during roundtable discussions, we present strategic intervention points that can effectively drive UK and international systemic resilience to cascading transnational climate risks.

- Embed systemic resilience across UK policy and reframe risk communication. Create a national resilience framework with clear metrics, targets, and cross-government leadership.

- Prioritise global-local interdependence and protect critical supply chains. Recognise that climate vulnerabilities abroad—especially in Emerging and Developing Economies (EMDEs)—directly impact UK stability. Map and secure the UK’s food, medicine, and energy supply lines from transnational, cascading climate shocks and embed resilience clauses in trade agreements.

- Mobilise finance for adaptation. Reform financial regulations to support resilience-oriented investments, incentivise public-private risk sharing, and adopt clearer metrics to unlock private capital flows. Direct resources to resilient infrastructure projects in EMDEs.

- Leverage foreign policy. Align UK diplomacy and trade with resilience-building in climate-vulnerable partner countries. Adopt a vision prioritising building of climate resilience in EMDEs as a key policy objective, alongside national interests and trade strategies.

- Empower communities. Invest in local adaptation infrastructure, especially in disadvantaged areas, and mainstream inclusive planning tools. Engage with communities to empower those most affected by risks and develop locally led solutions both in EMDEs and at home.

This opinion piece reflects the views of the author, and does not necessarily reflect the position of the Oxford Martin School or the University of Oxford. Any errors or omissions are those of the author.